In early April last year, a propaganda piece by a certain Timofey Sergeytsev appeared on the Russian state information (i.e. propaganda) resource RIA Novosti. The text is a good example of the gross human rights violations planned by the Russian leadership. The plans voiced in it are no longer destined to come true. And therefore, Ukrainians, if they are interested to know what was originally planned for them, should study the reports of human rights activists of the second Russian-Chechen war.

A war that is not over in strictly legal terms, spilling over first into the Russian regions adjacent to Chechnya, continuing in Syria and now flaring up with renewed vigor in Ukraine.

The same propaganda piece stated that Ukrainians who take up arms “should be destroyed on the battlefield as much as possible” and that no distinction should be made between the military personnel of the Ukrainian army and the militias from the territorial defense. But “a significant part of the masses of the people is also guilty”. The text labels most Ukrainians as “passive Nazis” and “accomplices of Nazism”. If we compare it with the Russian-Chechen war, then this term is a copy of the term “accomplices of the terrorists”. Using the same propagandistic wording, Russian power structures abducted tens of thousands of residents of Chechnya not engaged in armed hostilities.

Many of them were killed, some of them were convicted on fabricated criminal cases after torture and are kept to this day in prisons and colonies. Only a small part of the captured managed to escape from the hands of the alleged law enforcement officers. Often for ransom. Another 5-7 000 are listed as missing. And this is despite the fact that the population of the Chechen Republic at the time of active hostilities in the beginning of the 2000s, approximately constituted 700-800 000 people.

But no figure can highlight the anguish and despair which the relatives of the abducted had to go through, the lies and hypocrisy that they had to listen to and endure over many years of searching. What the “popular masses” went through in the process of “denazification” of Chechnya in the Russian way is best seen in concrete examples.

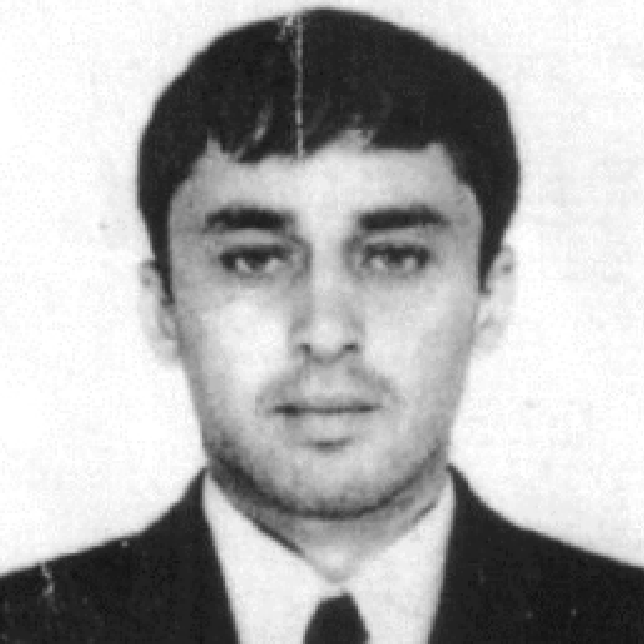

For instance, the Database of the Natalia Estemirova Documentation Center at the Norwegian Helsinki Committee describes the story of the illegal detention and subsequent disappearance of Yusup Mezhiev, a 29-year-old resident of the village of Starye Atagi. On 23 June 2002, he left for Grozny in the morning. A separate unit of the police escort service, where he worked with the rank of foreman, was stationed there. But at the Russian post at the entrance to the city he was detained.

Armed people in masks, identified in the materials of the criminal case as “unknown FSB officers”, said that some circumstances related to him needed to be clarified, and they put a bag over his head. People passing through the checkpoint later said that Yusup Mezhiev was put into a UAZ car and was taken away towards the center of Grozny. As it turned out, to the military commandant’s office. Some of the local residents saw him in handcuffs and informed the village. But the officers of the commandant’s office “reassured” the relatives who arrived: Yusup Mezhiev was not delivered to them, and they did not know anything about his detention.

For more than ten years, the Russian authorities have only been creating the appearance of investigating this incident. Relatives’ requests and statements were answered promptly each time, within the time limits stipulated by the procedural code, informed about the resumption of the case, and time and time again, strictly in accordance with the law, informed about its suspension.

The game of ping-pong went on for weeks, which then turned into months, and months into years, without any significant result in clarifying the further fate of an officer of the Russian police force detained in front of witnesses at an official Russian post. Albeit Chechen by nationality, he belonged to a rank shared by numerous investigators, prosecutors, and the entire vertical of Russian power, from the occupying power, up to federal officials in the highest Moscow and even the Kremlin offices.

Relatives appealed to all authorities available to them, tolled all the bells, but did not get an answer to their simple questions: why was Yusup Mezhiev detained that day and where was he taken?

At the same time, the same investigators were not reluctant to conduct additional investigative actions. “Do you want the military men who were on duty to be interrogated again? Yes, easily – no problem!”

And then, after the time allotted for this, they would send an official letter to Starye Atagi in an envelope with postal stamps and with bold official stamps on both sides: those on duty at the post have been interviewed, the abductors were unknown to them, and they did not know where Yusup Mezhiev was taken.

“You want to listen to the witnesses of the detention again, you say? That makes sense, not difficult at all, maybe they will say something new that will speed up the investigation?”

And again, an answer that looked important on the outside but was worthless in content would arrive to the relatives’ home address: there is nothing significant in the testimony of witnesses, and therefore, unfortunately, there are no grounds for resuming the investigation.

The investigation in the framework of the criminal case on the abduction of Yusup Mezhiev was suspended for the first time in September 2003. The reason was the inability to identify the perpetrators. The relatives protested this decision, and the investigation was re-opened a few months later. Subsequently, it was suspended every three months: two months, as it were, an investigation, then suspension due to the lack of new data, then a protest from relatives to supervisory authorities, and again an official imitation of a two-months long investigation.

The lengthy efforts by the relatives of the abducted person lasted until January 2011, when they, in despair, decided to go to court with a complaint about the inaction of the prosecutor’s office. But the court also continued the game of evading criminals, who, if desired, could have been identified in the blink of an eye. The court dismissed the complaint, referring to the fact that the investigation allegedly had been resumed and that its results had to be awaited.

But there was neither strength nor sense to wait further – the wife, brother and son of the abducted person appealed to the European Court of Human Rights. In the ruling in the case “Temersultanova and Others, No. 41884/11” (https://www.srji.org/resources/search/yandaeva-i-devyat-drugikh-zhalob-protiv-rossii/), the Russian state was found guilty of ineffective investigation into the circumstances of the abduction of Yusup Mezhiev, in violation of his right to life. They were also found guilty of inflicting suffering on his relatives, who for years had to endure indifference, lies, hypocrisy and outright mockery by the investigative authorities of the Russian Federation.

The European judges, acting solely within their competence, did not note in this decision (as, by the way, neither in other cases on Chechnya) that the Russian authorities quite effectively channeled the desire of relatives to find out the truth about the fate of the abducted person. They also did not note that the actual goal of all this never-ending investigation is:

a) avoiding responsibility for the perpetrators of the crime; and

b) suppressing the will of those who want to know the truth.

Physical terror against some, and emotional and legal terror against others – this is the essence of what Russia is doing in occupied Chechnya. However, we can also add to this the ever-increasing Russification encroachments on the indigenous population, including making classes in the Chechen language in schools an elective subject, a ban on use of the language in kindergartens and nurseries, the abolition of elections as an institution of popular will at all levels, and feudalization by bringing to power people who have never been elected anywhere but merely on the basis of belonging to a certain family.

In this way one can in general terms imagine the policy of “denazification of the masses”, which, referring to plans in Ukraine during the outbreak of the war, were confidently and shamelessly poured out on the propaganda channel RIA Novosti by Putin’s publicist Timofey Sergeytsev a year ago.

This article is based on the materials of human rights organizations, collected and systematized in the electronic database of the Natalia Estemirova Documentation Center (NEDC).

Contact us

Employee