Especially in a non-democratic country like Azerbaijan, where no separation of powers and no independent judicial system exists, they should acts as a democratic judiciary, highlighting human rights abuses and demanding an end to them. A serious increased international attentions and a renewed burst of efforts for the release of political prisoners is must.

by www.nopoliticialprisoners.org December 1, 2016

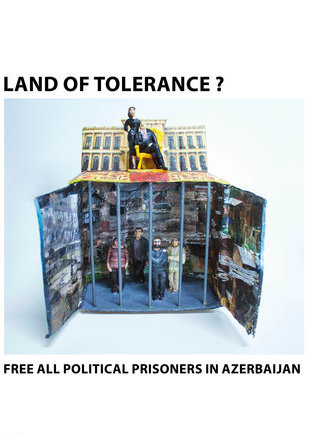

December 1, 2016: Many political prisoners rot in the jails of Azerbaijan, where the imprisonment appears to be ordeal that one has to go through in the fight for freedom and human rights. Like it was in the Soviet era, they are thrown in jail for political beliefs that do not coincide with the views of a repressive regime, not afraid to speak up and act publicly against the authoritarian policies of the government.

Find the list of political prisoners here.

Taking political prisoners is not only President Ilham Aliyev’s way of silencing critics. The prisoners also serve as “assets” in his dealings with the international community. Whenever warmer relations with the West are needed, Aliyev frees some of them. Especially, the existence of high-profile political prisoners, such as the currently imprisoned prominent opposition leader Ilgar Mammadov, ensures that the Azerbaijani regime always has a hand to play when it wants something from the West. That is how the activists in Azerbaijan continue to be used as bargaining chips in these dirty political games with the West.

But exactly how many such prisoners are there in today’s Azerbaijan? It has been a contested question as various lists used to appear in the past and occasionally differed from one another. Some find the discussions irrelevant, arguing that numbers of the political prisoners are not important, the essential is to have no such prisoners at all.

One cannot find a single reference to the exact number of political prisoners in Azerbaijan in any recent official and international documents, such as those of the Council of Europe Parliamentary Assebly (PACE) or the EU’s diplomatic service EEAS. These institutions have never stated how many Azerbaijanis they consider to be political prisoners. In fact, they even hardly ever used the phrase “political prisoners” in their reports on Azerbaijan unlike those concerning Belarus, even though the Azerbaijani government’s systematic use of criminal prosecution as a tool for political retaliation is a well-documented problem.

Counting political prisoners has never been a hassle-free process, it even cost the freedom of many courageous activists. In late July 2014, when a group of activists compiled the report on the cases of political prisoners, authorities rounded up most of them and sentenced to lengthy imprisonment on fake charges.

The government has also gone to great lengths to obstruct the international engagements on counting political prisoners. Back in January 2013 January, Azerbaijan’s practice of criminally prosecuting its critics came under a rare spotlight at PACE. The report was prepared by the German parliamentarian Christoph Strässer, who had drawn up a list of 85 political prisoners in Azerbaijan. Weeks before the voting at the PACE, the list included 50 names, as 35 of the prisoners on the list were released.

To conceal the numbers of the political prisoners, the Azerbaijani authorities had gone to unprecedented lengths to hinder rapporteur Strässer’s work between 2009-2013, refusing him access to the country and rejecting the mandate as unjustly singling out Azerbaijan. As a result, Strässer was compelled to produce a report without being able to visit Azerbaijan. His detailed account on 50 political prisoners in early 2013 was convincing and authoritative, as a result of his extensive, in-depth consultations with Azerbaijani lawyers, as well as local and international human rights groups.

The report, which would have been crucial in the Council of Europe’s efforts to hold Azerbaijan accountable for the issue of political prisoners, was defeated in a vote, mainly as a result of the intensive lobbying of the Azerbaijani government.The vote caused Azerbaijan’s pro-governmental MPs at PACE to erupt in a victorious cheer one might expect from sports fans following a win by their favorite team. The Aliyev regime clearly interpreted the voting result as carte blanche to carry on with politically motivated arrests – which accelerated from this point. The repressions going on until this day.

Cat-and-mouse game

When it comes to freeing some political prisoners, Azerbaijani regime knows how to skillfully play the cat and mouse game with the West. The government practices a revolving-door policy with critics, locking them up and releasing them when it is expedient. For instance, some 15 political prisoners received pardons before president Aliyev’s trip to a nuclear-security summit in Washington, DC, earlier this year. Despite of the international appreciation, it was hardly a sign of liberalization of Aliyev’s ossified autocracy. Those who regained their freedom continue to live under a shadow: None of those released political prisoners had their sentences vacated until today, several face travel restrictions, and others left the country fearing further politically motivated persecution.

At the same time as some critics were let out, however, government is still busy replacing them: those challenging president Azerbaijan’s autocracy are tossed inside on spurious criminal and administrative charges to prevent them from carrying out their legitimate work. Since the pardoning decree, at least 8 activists were arrested and they mostly earned the same trumped–up “drug possession” charges that were pinned on some of those released in March.

New unified list of political prisoners: Who are behind bars?

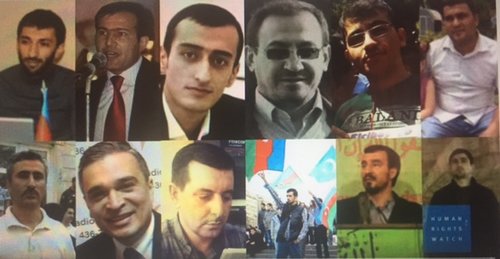

This week, a group of courageous activists, including former prominent political prisoners Khadija Ismayilova, Intigam Aliyev, Rasul Jafarov, Anar Mammadli and several lawyers reported a shocking total of 119 cases of political prisoners; a sharp increase from the 50 detailed in Strässer’s report of 2013. This unified list exposes the discrepancy between human rights obligations and the systematic violation of these commitments occurring in Azerbaijan today.

The 111-page comprehensive and unified report, details 119 prisoners’ cases, which the authorities have sentenced political and civil activists, journalists, bloggers, and peaceful protesters to heavy prison terms. In addition, the cases of another at least 25 people are being currently monitored as potential political prisoners.

The report categorizes these prisoners under “human rights defenders”, “journalists/bloggers”, “youth activists”, “political party activists”, “lifetime prisoners” and “religious activists”.

Among many, the appalling experience of two youth activists with the NIDA pro-democracy group, Giyas Ibrahimov and Bayram Mammadov, highlights how brazenly the regime tortures and throws them into lengthy imprisonment. They were arrested in May 2016 for painting antigovernment graffiti on a monument to the country’s former president Heydar Aliyev, the father of the current president. When detained, the policemen had beaten them after they refused to apologize at the monument in front of TV cameras in exchange for their freedom. While beating them, the police forced them to take their pants off and threatened to rape them with truncheons and bottles if they did not confess to drug possession. Following the abuse, they confessed to drug possession, the fabricated charge that the regime most often uses to arrests its critics. Ibrahimov was sentenced to 10 years on drug charges, Mammadov’s show trial is still ongoing.

Or, take the cases of the imprisoned members of the opposition Popular Front Party, which has become a special target of the regimes persecution in recent years. At least 12 leading and rank-and-file activists of this major opposition party are either on trial or serving harsh prison terms. Among them are Murad Adilov and Elvin Abdullayev, who are yet another victims of the trumped-up drug possession charges.

Some of those political prisoners also include prisoners on trial in the so-called Nardaran cases, which concerns state allegations that Taleh Bagirzade, an imam who had previously been jailed on politically motivated charges, conspired with others to overthrow the government. All of the detainees without exception reject the charges as fabricated; several say they have been subjected to incredible torture in an attempt to induce them to incriminate themselves, fellow defendants, and respected opposition leaders.

The list includes many similar sorrowful stories.

What next after the list of political prisoners?

The key challenge is how to use the list of the political prisoners in order to ensure sufficient political pressure on the Azerbaijani government to do what it takes to rectify the problem. For today’s political prisoners, it is particularly important to know that they are not forgotten and that their sacrifice is being recognized. How the list could ensure that today’s much-needed spotlight on Azerbaijan’s political prisoners translates into real change for those suffering persecution at the hands of the regime?

It is vital to remember that the fate of political prisoners directly and proportionally depends on international attention, solidarity and action. With so many innocent activists behind bars, no one is seriously discussing their fates. The absence of international pressure leads to more impunity for the perpetrators, both individual officials and repressive state institutions.

The main responsibility lies with Azerbaijan’s international partners, including its fellow member governments of the Council of Europe. They need to make clear just how the release of those held on politically motivated charges are to a successful relationship. Individual assembly members who care enough can and should help make this happen. They should take up the issue in their domestic parliamentary settings and urge their elected leaders to make sure it features high in their countries’ bilateral relations with official Baku.

Appointing a rapporteur on political prisoners in 2009 used to reflect the institution’s recognition that Azerbaijan’s record on political prisoners is a serious problem. However, in a great disappointment, it failed to continue the mandate and could not stand up against Azerbaijani regime’ bullying tactics and wide lobby activity.

Thorbjorn Jagland, the Council of Europe Secretary General in his role as the institution’s highest-ranking spokesman, should play a key role to play in highlighting the issue of political prisoners and making clear it remains a priority concern for the institution. Azerbaijan’s continued detention of opposition leader Ilgar Mammadov, despite the European Court judgment ordering his release since 2014, has long become a serious indicator for the lacking effectiveness of Council of Europe. Although Jagland had launched official inquiry into Azerbaijan’s implementation of the European Convention on Human Rights exactly a year ago, it has not brought us a single step further.

Jagland’s special envoy Philippe Boillat has yet to visit Azerbaijan and reportedly the Azerbaijani government obstructs his visit and refuses cooperation. The government has turned deaf ears to the calls and repeated condemnation of the Committee of Ministers on the imprisonment of Ilgar Mammadov. While Azerbaijan undermined the credibility of the entire body of the Council of Europe in past years, it should now lead to its expulsion from the organization. Only such principled political stance, coupled with firm and sustained political pressure can ensure the imperative rights reform in the country.

While the EU occasionally has been vocal of Baku’s serious failures to meet its human rights commitments, the criticism appears to have had no or little impact on its relationship with the government. EU should demonstrate same principled approach that it used to show in the cases of Belarusian political prisoners. It should impose visa bans on senior government officials such as ministry of interior officers and prosecutors responsible for the unjustified criminal prosecutions of human rights defenders, journalists and activists in retaliation for their peaceful exercise of their rights.

The international actors, who care enough on Azerbaijan, must ensure that its actions match its words: They should refer to the list of political prisoners of Azerbaijan if they are serious about their stated commitment to promote and protect democracy and human rights in Azerbaijan. Especially in a non-democratic country like Azerbaijan, where no separation of powers and no independent judicial system exists, they should acts as a democratic judiciary, highlighting human rights abuses and demanding an end to them. A serious increased international attentions and a renewed burst of efforts for the release of political prisoners is must.